If private archives could talk

A glimpse inside Westpac’s corporate archives uncovers rarely-seen records.

Most Australians would recognise Mary Reibey’s face from our $20 banknote.

Many may also know her rags to riches tale, which charts the story of an orphan, transported as a convict in 1791 for horse theft at age 13, who went on to become one of the most successful entrepreneurs in the young colony of New South Wales where streets were later named in her honour.

But I would hazard a guess that almost no-one – not even the most committed students of Australia’s history – know the half of this great tale. Or for that matter others, such as bank branch heists by Ned Kelly.

That’s because some of the most fascinating evidence of these stories are not on the public record, but in Westpac’s corporate archives.

Established in 1955 under the purview of notable economic historians, and one of only a handful of corporate collections in Australia, if you laid each shelf of Westpac’s archives end to end, they would stretch for almost six kilometres. Added to that is our photographic collection with more than 10,000 images, and 5000 or so architectural plans.

Private collections play a role by storing what public ones don’t. Reibey, for example, was one of the first shareholders and customers of the Bank of New South Wales – which became Westpac. Her rarely-seen bank passbooks, preserved in our archives, contain incredible details of her commercial and trading activities, including who she did business with, how much it was worth, what her investment returns were – all providing insight into how she built her vast wealth.

It shows, for example, she went into business with the likes of Gregory Blaxland – of Blaxland, Lawson and Wentworth fame – who mapped the travel route for the colonists over the Blue Mountains and went into road building. She even made money from the fledgling bank, having rented one of her many properties to the bank as its first premises for £150 per year.

Detailed records such as these are just some of the truly fascinating insights into our nation’s tapestry that I help store as part of my – admittedly – slightly unusual sounding job.

But it’s often only by drawing upon both private collections and extensive public records that we can glean the full story of our complex, multi-faceted society and culture.

A good example is the First World War, a transformative moment in Australia’s history – and especially relevant as we commemorated its centenary – for which the “record” is split between public and private holdings. On one hand, public sector records held by the National Archives include service dossiers containing enlistment dates, illnesses and troop movements. On the other, private records include letters, diaries, photographs and mementoes – items which capture detailed, first-hand experience.

Indeed, Westpac’s collection contains descriptive letters written to managers by employees who served on the front line, and detailed HR reports which document each serving employee’s safe arrival home, the type of convalescence they needed and the support required to readjust to post-war life and work.

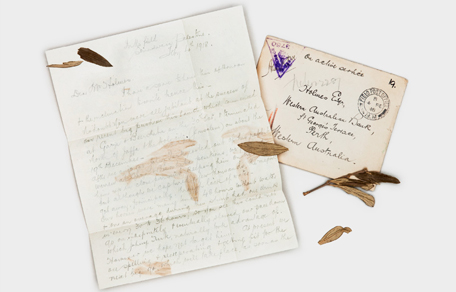

This letter from Alan Love – a bank officer from Mount Lawley who served with the 10th Light Horse Regiment in Palestine – to General Manager Henry D. Holmes, contains vivid descriptions of the action around Gaza and Beersheba in 1917 and a sprig of olive leaves. (Westpac Group archives)

Private collections also illuminate our nation’s creativity, the migrant experience, women’s history, the LGBTQI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, and intersex) community story, and small businesses – the pockets of struggles that often went on in workplaces before they came to the national consciousness. Little of this is captured in the public sector National Archives, and yet all, to differing degrees, is integral to the evolving Australian culture and society.

But unlike the extensive collections held publicly, private corporate collections are rare in Australia. Only a handful of businesses hold their own archives, including BHP and some of the banks.

This is largely because – unlike the public sector – it’s not a legal requirement for a business to maintain its records for the long term, except for certain regulatory records. In stark contrast, specific laws – such as the State Records Act NSW (1998) – set out the recordkeeping requirements for every public sector department and agency at state and federal levels, including what records must be retained, for how long and where. This practice has its roots in the French revolution, where the records of interaction between the government and citizens are collected to ensure accountability and transparency of decisions, a cornerstone of any democracy.

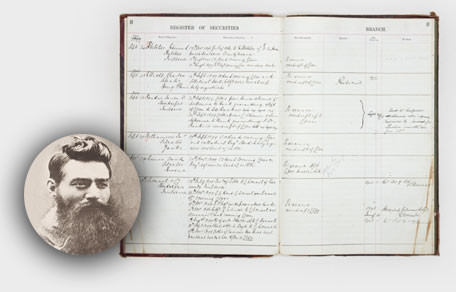

The Jerilderie branch ledger noting details of the 1879 robbery by the Kelly gang (Westpac Group archives), with photograph of Ned Kelly, c.1880 (Collection of State Library of Victoria).

Notable gems in Westpac’s archives besides Mary Reibey’s passbooks include the ledger from the Jerilderie bank branch with meticulous entries detailing the 1879 heist of the notorious bushranger Ned Kelly and his gang. Coupled with this are board meeting minutes describing improvements needed to security of branches and safety of staff in the face of escalating bank robberies. Together, these records provide a context generally unexplored in the historical retelling of these infamous events.

Similarly, records of the bank’s interaction with other start-up businesses which have become synonymous with Australia’s collective memory – Qantas and AGL spring to mind – provide a level of detail about their evolution not publically present.

Everyone interested, whether economic historians or documentary makers or not, should come take a look at the archives for a glimpse of untold history. They tell a broader story than just about a bank.