Saving souls and silver during New Guinea campaign

The stronghold was the only remaining part of the bank branch at Wau, New Guinea, after bombing raids. (Damian Parer)

It’s hard to imagine going from a normal bank job one day to fleeing a bombardment of enemy fire the next.

But that’s exactly what happened 80 years ago for staff of the Bank of New South Wales (which became Westpac) stationed in branches across New Guinea during the second world war.

I recently dug up astonishing details of the plights of these staff members, through letters and photos held in the bank’s archives, documenting the chaotic evacuations right across the territories, then administered by Australia, as Japanese forces invaded in early 1942.

What amazed me as I pored through these treasures was the lengths taken by staff to try to protect the bank’s and customers’ assets, while their own lives were in such danger.

These staff were mainly Australian ex-pats, posted for short-term stints across the bank’s New Guinean branches, a network which had grown to eight since the first opened in the capital Port Moresby in May 1910 primarily to service traders in the region.

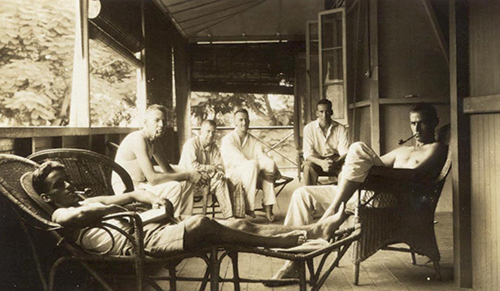

Before the war, Bank of NSW Port Moresby staff share a lazy Sunday, c.1935. (Westpac Archives)

While a couple of the branches had closed in the early days of the Pacific War from 1940, the other six remained open until Japan’s campaign started in earnest in January 1942, forcing civilians and Allied soldiers to flee the territory.

The first township to be captured by Japan was Rabaul, on the island of New Britain about 600km to the east of mainland New Guinea, where the bank had a branch, since 1926. Over-run by the massive Japanese fleet of bomber aircraft, destroyers and submarines, the town’s administrators gave the order on January 23 that it was ‘every man for himself’. The bank’s eight membered staff and throngs of others fled, some enduring epic treks through the rugged island terrain hoping to be rescued.

Incredibly, two senior branch staff, Bill Clarke and Ron Skillen, escaped in a small boat during the night, taking with them the bank’s records and £5299 in banknotes. They piloted the boat almost 1800km through hazardous waters, mostly patrolled by Japanese warships, delivering themselves and their cargo to the relative safety of Townsville in Queensland.

Among the other Rabaul-based staff, two escaped by foot to the north coast where they found a boat, made their way to an outer island and were fortunate to board a vessel owned by the former Australian shipping company Burns Philp which evacuated around 200 civilians to Cairns; and the ledger-keeper made his way south and was picked up by a boat evacuating to Port Moresby.

Two others weren’t so fortunate. As they manned a gun on the foreshore they were strafed by a Japanese aircraft and were never seen again.

Before the war, Bank of NSW Wau branch in 1933. (Westpac Archives)

Meanwhile, on the same day, in the town of Lae, on the northeast coast of the mainland, Ken Diamond, the manager of the local branch, which had opened only two months previously, was as shocked as the rest of the community when almost 40 Japanese bombers and fighters unexpectedly opened fire on the town.

After the hour-long air raid, the community agreed to escape by foot, making the arduous 160km trek to Ramu in the hinterland.

Before fleeing, Diamond made the decision to protect the bank’s assets and records by burying them in two cash boxes near a tree. As he explained in a letter to senior staff, “I felt that under the circumstances I could not carry them out and could not see that I had any opportunity of sending them out.”

As it transpired, Diamond was eventually safely evacuated to Australia, but the buried cash boxes were never recovered, and no trace was ever found of the bank building or its safe. They had been obliterated by repeated bombings, not only by the Japanese but also the Allied forces when they re-took the area.

At the same time, just 150km south of Lae at the Wau bank branch, which had been established in 1929, the manager Bob Byrne was faced with similar dilemmas as evacuation orders were given.

Discovering that an old plane was being prepared to fly evacuees to Port Moresby, he put the bank’s records and assets, including around £1900 in notes, in an iron trunk ready to transport. Told that it was too heavy, he reduced the load by yanking covers from ledgers and returning the bank’s silver ingots to the branch stronghold.

Bob Byrne (centre) removing silver ingots from the Wau stronghold, the only part of the branch to remain after bombing in 1942. (Westpac Archives)

After escorting the iron trunk to the Port Moresby branch manager to be on-sent to Brisbane, Byrne was preparing himself to return to Australia when he received a rude shock. He was arrested by two military police and flown back to Wau for questioning. Although the matter was straightened out, he stayed on in Wau to serve with the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles.

Less than two months later, the Wau branch was destroyed in an air raid, but its stronghold – in which Byrne had safeguarded the silver – survived the blast. Weeks later, the silver was urgently needed by the administration to pay carriers for supplies, but Byrne had given his keys to another staff member who’d been evacuated.

With the only remaining option to break into the stronghold, Byrne tapped the shoulder of an NGVR member who’d been trained as a welder. After wielding an oxy-acetylene torch for five tiring hours, this man cut open the stronghold door, and the carriers received their pay. More than a decade later when a new bank branch was built in 1953, it incorporated the old stronghold – a silent reminder of the past.

The new branch built at Wau in 1953 incorporated the original stronghold into its design. (Westpac Archives)

These are just a few of the harrowing stories of almost 30 bank staff stationed across New Guinea during the intense campaign, which lasted until the Japanese forces were defeated by the Allies in 1945.

Some of these bank staff were among 4445 Bank of NSW team members – and almost a million other Australians – to enlist during the second world war.

They show how in remarkable circumstances, ordinary people can step up in remarkable ways.

Lest we forget.