Premature end to property downturn will add to renters’ pain

Apartment blocks at Breakfast Point, Sydney. (Getty)

If you think Australia’s squeezed renters can make the switch and purchase properties that have fallen in value due to the rise in interest rates, then think again.

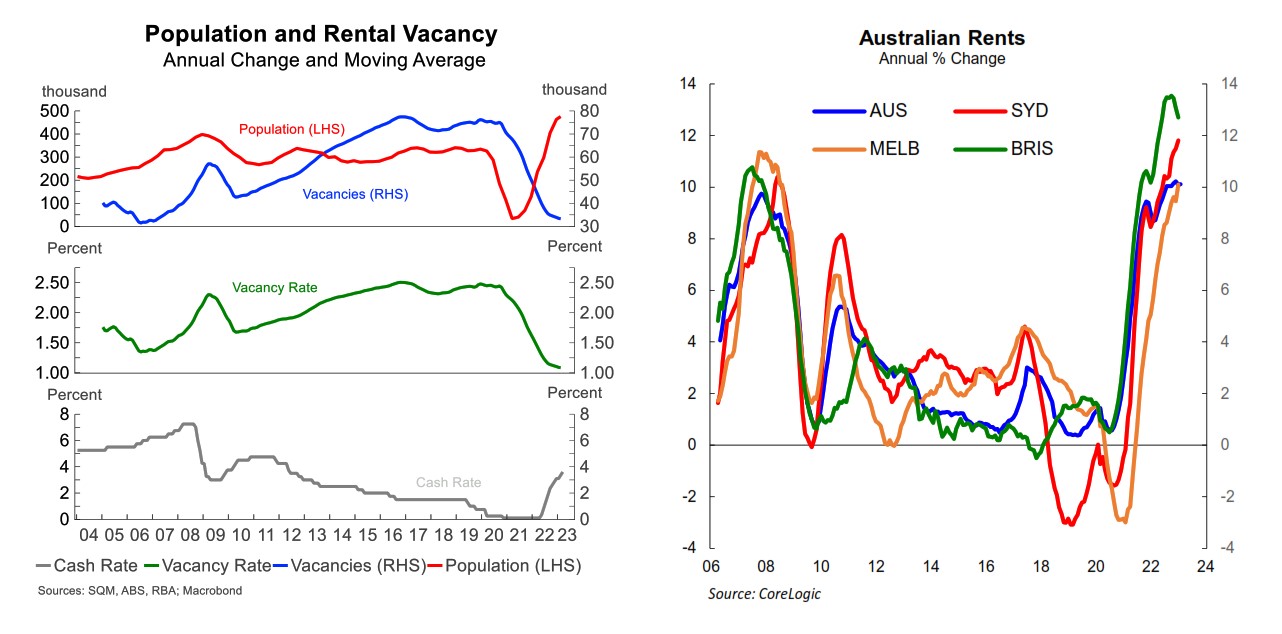

We expect record low rental vacancies and continued strong population growth to drive advertised rents up by around 11.5 per cent this year – the fastest pace on record.

Typically, in an environment where the Reserve Bank of Australia had lifted the cash rate at ten consecutive Board meetings prior to April’s pause, you would expect dwelling prices to remain under pressure.

And as prices fall, they can offer an escape route for renters as the move into home ownership comes within reach.

However, we are not living through a typical period. Demand, underpinned by record levels of inward migration, is pushing up against low volumes of housing available for sale.

In March, housing prices recorded their first rise in eleven months. History tells us that the bottom of the market usually comes one or two quarters after it becomes clear that the tightening cycle has ended. But early signs suggest that bottom might happen sooner this time around.

RBA Governor Philip Lowe said this week that he sees rental stress as at least as big an issue as mortgage stress, and warned that not enough new housing was being built to keep pace with strong population growth.

However, there are few short-term solutions to increase housing supply. Building approvals have fallen sharply: down over 45 per cent from the cycle peak in 2021.

Once approved, it takes time for construction projects to get off the ground and be completed, leaving long lag times and mismatches between demand and supply.

In fact, we expect the supply of new stock to respond with a longer than usual lag given the headwinds hitting the construction sector from unprofitable fixed price contracts and rising material and labour costs.

Financial difficulties faced by builders have been highlighted by the collapse of Porter Davis and Lloyd Group in recent days, which has further dented confidence in the industry.

The squeeze is not just confined to the builders: it also flows to downstream industries and suppliers, including tradies and sub-contractors.

And as the supply response takes time to gather momentum, demand for housing will continue to increase, with Treasurer Jim Chalmers confirming last month our expected net overseas migration forecasts of at least 335,000 for 2022-23.

Given these dynamics, there’s little prospect of the rental squeeze easing anytime soon, and that has implications for the broader economy. As the RBA notes, if the one-third of households that rent were to sharply reduce their non-housing consumption, it could contribute to a much more material downturn.