The best places to be a working woman in 2025

This article was originally published by The Economist on 5 March, 2025.

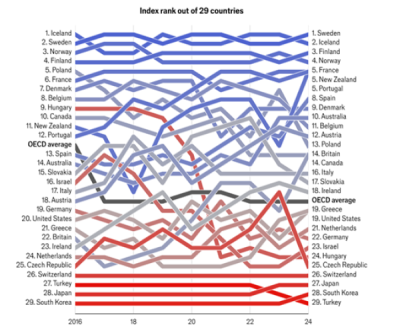

Each year, to mark International Women’s Day on March 8th, The Economist publishes the glass-ceiling index. It compares working conditions for women across the OECD, a club of 29 countries. The index is based on ten measures—from labour-force participation and salaries to paid parental leave and political representation. The charts below show how each country performed in 2024.

Sweden came in first place, ending Iceland’s two-year winning streak. The Nordics always perform well on our index, which we have published for the past 13 years, thanks to policies that support gender equality and working parents. At the opposite end of the ranking, South Korea—which had always come in last place—advanced to 28th, pushing Turkey down to the bottom spot. New Zealand was our most improved country, rising eight places to fifth.

A closer look at our ten criteria shows which factors are driving these movements.

Start with education. Women across the OECD graduate from university at much higher rates than men. As of last year, 45% of women had a degree, compared with 36.9% of men—a slightly bigger gap than in 2023. Over the past decade, around a third of people taking the GMAT, the de facto entrance exam for an MBA, have been women. In 2024 that share increased modestly to 36%, led by increases in Finland, Estonia and New Zealand.

Despite these trends, labour-force participation remains lower for women. According to the latest available data, 66.6% of working-age women had a job compared with 81% of men. These rates vary considerably by country: in Iceland and Sweden, for example, more than 82% of women work, whereas in Italy the figure is just 58%.

The lower participation rates hinder career progression, which in turn affects the gender pay gap. Across the OECD median wages for women are still 11.4% lower than they are for men. In some countries, including Australia and Japan, the gap is growing wider.

The next three indicators broadly track the progress of women in business and politics. The share of company board seats held by women has increased from 21% in 2016 to 33% today. In New Zealand, France and Britain women now hold nearly the same number of board positions as men. Similarly, in Sweden, Latvia and America women now fill almost half of all managerial positions. Britain performed particularly well on these indicators compared with previous years, sending its overall score higher.

Representation in politics is also edging up across the OECD. After last year’s election extravaganza, women’s share of seats in parliaments ticked above 34% for the first time in the index’s history. In Britain the election of an additional 43 women MPs in July 2024 raised their share from 35% to 41%. Just 16% of Japanese lawmakers are women, although that is a record high for the country.

Our final three indicators cover the effects of starting a family (these have a lower weighting in the ranking since not all women will have children). Because mothers continue to carry out most child-care duties, generous parental leave and affordable child care can significantly increase their participation in the workforce. By these measures America performs particularly badly. It is the only rich country that does not provide any nationally mandated parental leave, and child-care expenses exceed 30% of average wages. Only New Zealand and Switzerland have higher relative costs, at 37% and 49% respectively.

More generous policies exist in Hungary and Slovakia, where mothers receive the equivalent of fully paid leave for 79 weeks and 69 weeks, respectively. Leave for fathers is also important—it prevents companies from discriminating against women and helps share the burden of child care. Surprisingly, Japan and South Korea have the most generous paternity-leave policies in the OECD (though few new fathers choose to stay at home).

The glass-ceiling index is a broad and imperfect snapshot of the workforce. But it does help to show how countries perform on a consistent group of indicators over time. Although women are still struggling to break through the glass ceiling, most countries are at least changing for the better.

The articles may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third-party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for third-party material. Further, the information provided does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and so you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your personal objectives, financial situation and needs before acting on it.