On average, men can expect to spend 20 years kicking back

This article was originally published by The Economist on 27 March, 2023.

Over the past week protests in France against the government’s pension reforms have intensified. On March 24th, after a mob set fire to the façade of Bordeaux’s town hall, Emmanuel Macron, the president, postponed a four-day state visit by Britain’s monarch, King Charles III. France is no stranger to protests. But Mr Macron’s decision to force through an increase in the pension age from 62 to 64 years has aroused particular ire.

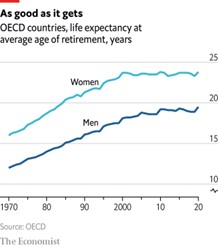

All rich countries with welfare states will, in fact, need to make similarly unpopular choices. The combination of fewer births and longer lives means that the old-age dependency ratio—the proportion of people aged 65 and older to those aged between 20 and 64—is expected to rise from one in five in 1990 to one in two by 2050 across the OECD, a club of mostly rich countries. And the time people spend in retirement has shot up in the past 50 years.

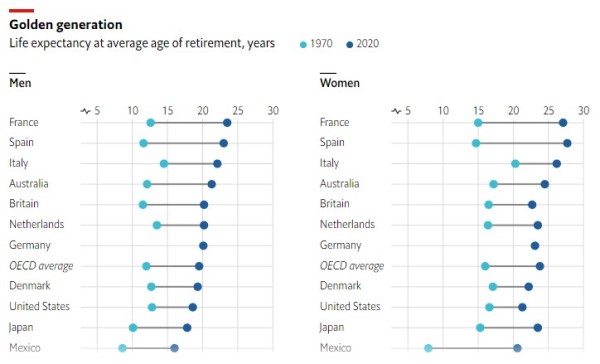

In 1970 men, on average, retired at 66 and could expect to live another 12 years. In 2020 they retired at 64 and had 20 years ahead of them. French men, in particular, have some of the lengthiest retirements—some 25 years on average, double that of the previous generation (see chart). By contrast, although their life expectancy at retirement has also doubled over the same period, Mexican men today spend 16 years in retirement.

Faced with an inevitable demographic crunch, how do governments reform pension systems without facing a revolt? Some 22 oecd countries employ “automatic adjustment mechanisms” which, for example, link life expectancy to statutory retirement age, or tie pension benefits to the size of the working population. The oecd recommends employing these tools to prevent pensions from crippling governments as populations age, while also reducing the political cost of pension reforms—a cost that Mr Macron was willing to bear, perhaps, because he cannot be re-elected after his second term as president.

Britain, by contrast, has in recent years raised the state pension age with little fuss. The French have more to lose: state pensions account for a generous 60% of an average individual’s final earnings in France, whereas in Britain they account for just 20%, with private pensions providing further benefits. From the 1940s to 2010 Britain’s state pension age was 60 for women and 65 for men. Since then, the pension age for women has been equalised with men’s, and both have now been raised to 66. Two further increases will follow: to 67 by 2027, and to 68 in 2046. Legislation passed in 2014 now compels the pensions minister to publish reviews every six years; the next one is due in May.

Yet even in Britain it is not all plain sailing. The government is hoping it might raise the pension age to 68 sooner, but British life expectancy has flatlined in recent years, which may make it harder for it to do so. Britain is not alone. Legislation in 20 of 38 OECD countries mandates an increase in the retirement age over the coming decades; but faltering life expectancy could make such plans much less palatable.

Read more

Things you should know

The articles may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third-party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for third-party material. Further, the information provided does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and so you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your personal objectives, financial situation and needs before acting on it.