Where to find the world’s most wanted metals and minerals

This article was originally published by The Economist on 24 March, 2025.

The North Pole is a polarising topic. President Donald Trump has repeatedly said that he wants to acquire Greenland; he has not ruled out taking it by force. A delegation of American officials will arrive in the autonomous Danish territory later this week, ostensibly to learn about its culture and history. But what really motivates Mr Trump’s lunge for Arctic land is Greenland’s “rare earths”—a category of materials vital to modern armies and economies.

The president is obsessed with these strategic resources. A potential deal giving America some rights to rare earths that may be buried in Ukraine has been part of negotiations over continued military support to the country. Mr Trump likes “critical minerals”, too. A deal for them is in the works in Congo. He has also invoked wartime powers to boost mining at home.

“Rare earths” and “critical materials” are increasingly familiar terms. Yet they remain fuzzy, confusing things. Here’s a primer on the world’s most wanted metals and minerals.

There is no single definition for critical materials (ie, processed substances) and critical minerals (naturally occurring ones). America, the EU and Britain, for example, all have slightly different lists of the materials they deem “critical” (the table above uses a classification by America’s Department of Energy, DOE). Some are produced in large volumes for industry: aluminium and steel go into solar panels and wind turbines, and copper is used for everything from cables to cars. Cobalt, lithium and nickel make up battery cathodes for electric vehicles, and graphite is the main anode element.

Some of these materials were discovered only recently; others have been used for centuries. Antimony, known in ancient Greece for its medical properties and cosmetic use, is now used to flame-proof clothing, toys, cables and aircraft. Vanadium, named after a Scandinavian goddess, is a steel additive common in armours and nuclear reactors. It came to prominence around the turn of the 20th century. The critical-mineral family expanded during the cold war: cobalt, titanium, tungsten and others emerged as weapons material because of their hardness and high melting point.

Then there are rare-earth elements (see table above), a group of 17 minerals that share similar chemical properties. All except Promethium are classed as critical by the DOE. Neodymium makes magnets that go into EV motors and wind turbines. Yttrium and europium are used in television and computer screens, because they can display different, striking colours depending on the light source.

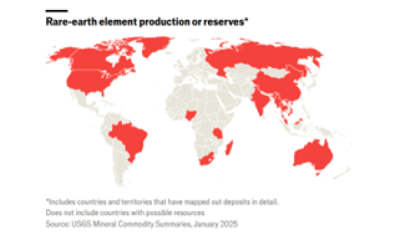

Rare earths are required in minuscule amounts. Finding them involves detailed exploration. Ukraine, for example, is thought to have significant rare-earth deposits, but conflict and investment gaps have hindered exploration. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) names 15 countries and Greenland as having actual reserves (see map).

The defining feature of critical materials and rare earths is not that they are necessarily rare in the earth’s crust. But they are often tricky to extract. For some, like copper, it is because they have been mined industrially for decades: a lot of big mines are old and being depleted; new mines tend to be in places that are politically unstable or hard to reach. Other critical materials, including rare earths, are hardly ever found in pure form. They must be separated from other minerals when dug out of the ground—a polluting process that devours energy and dollars (which is why Western countries have been hesitant to do it in their own backyards). At the same time, the market for such vital metals is often small, so countries that started producing them early on monopolise the market.

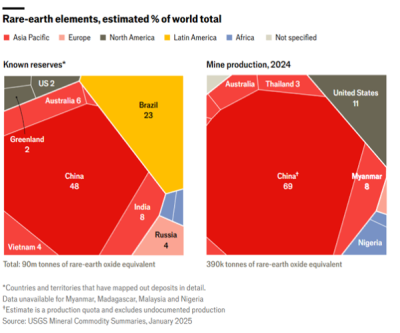

The refining of them is even more concentrated—usually in the hands of China. Chile accounts for 23% of the global copper production, but 44% of the world’s refined copper comes from China. One notable exception is nickel, half of which is mined (and often refined) in Indonesia. China is even more dominant in the production of rare earths (see charts below).

In the coming decades the rise of renewables and electric cars will require huge amounts of critical materials. The International Energy Agency, an official forecaster, estimates that if countries stick to their current climate pledges, annual demand for rare earths, nickel, cobalt and lithium will grow by 62%, 73%, 80% and 400%, respectively, by 2040. Even demand for copper, which is already high, is projected to rise by one-third over the period, to 37m tonnes.

That does not mean prices will reach the stratosphere. Some metals, such as lithium, were once thought to be rare but are in fact abundant and need less investment to dig out. That should keep prices lower. The supply of cobalt, a byproduct of copper, nickel and other metals, has risen rapidly even as demand for it is moderating because of changes in the technology behind EV batteries. For niche metals, like rare earths, supply disruptions or export restrictions, especially in China, may cause price jumps and shortages. But this could be solved with the right amount of investment in alternative suppliers, possibly subsidised or made by the state. The mineral facing the biggest disruptions is copper, which is required in much larger volumes. Miners are unlikely to be able to dig up enough of the stuff to keep up with growing demand. Politicians obsess over rare earths. But a much more common metal is the real problem.

The articles may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third-party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for third-party material. Further, the information provided does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and so you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your personal objectives, financial situation and needs before acting on it.