Without fanfare, the Philippines is getting richer

This article was originally published by The Economist on 23 April, 2024.

At Cotabato airport travellers must join a long sweaty queue to pay a tax of ten pesos (less than $0.20). Having handed over their cash—cards are not accepted—they must wait while three unhurried officials produce a paper receipt and stamp it. If they could avoid this hassle by having the tax added to their ticket, most would be delighted, even if the tax were ten times larger. Yet this simple reform has not happened, perhaps because it would cost those three unhurried officials their jobs.

Visitors to the Philippines have ample time to imagine ways to make its transport system less frustrating. When not queuing in rickety airports, they are often stuck in traffic. A typical commute from an outlying suburb to the centre of Manila, the capital, takes two hours, including nearly 30 minutes waiting for a bus to show up.

Yet things are improving. Roads are being paved, bridges built. In February the government picked a private consortium to revamp and double the capacity of Manila’s main airport. Later this year, it is expected to award contracts to modernise several regional airports, too. Manila is scheduled to have its first underground metro line by 2029.

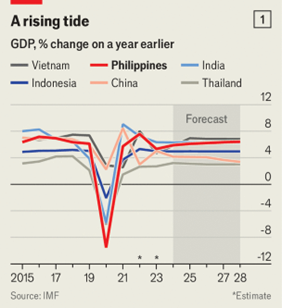

The Philippines is often an afterthought for investors: neither a giant like India nor a manufacturing superstar like Vietnam. But growth has been brisk at around 6% a year since 2012 (except during the pandemic). The economy has quietly boomed under a variety of regimes, from the liberal President Benigno Aquino (2010-16) to the thuggish President Rodrigo Duterte (2016-22). The run is set to continue under President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos (see chart 1). The World Bank says the Philippines will soon be an upper-middle-income country.

This might seem surprising, given its politics. Mr Marcos, the son of an appalling kleptocrat, was elected to the top job in 2022. He was helped by a massive campaign of disinformation aimed at rehabilitating the family name. Still, businesses rate his administration as more competent than his predecessor’s. Whereas Mr Duterte filled key posts with his drinking buddies from Davao, the city where he was mayor for many years, Mr Marcos has mostly appointed technocrats. His economic team is widely praised. “We appreciate the high level of collaboration between the government and the private sector,” says Alberto De Larrazabal, the chief financial officer of Ayala, a conglomerate.

Many of the reasons for optimism about the Philippines have nothing to do with who is in charge. The country is at a demographic sweet spot, with a bulge of working-age citizens. With half its people still living in the countryside, there is plenty of potential to shift from farming to better-paid urban jobs. But governance matters, too, and so far Mr Marcos is nowhere near as bad as many observers feared.

He has continued with his predecessor’s efforts to upgrade the infrastructure linking the archipelago’s 7,600 islands to each other and the world. Returns on investment in physical and digital infrastructure in the Philippines are higher than in neighbouring countries because “the gaps are huge”, says Ndiamé Diop of the World Bank. An improvement in respect for human rights helps, too. Whereas Mr Duterte loudly urged police to murder drug suspects, leading to thousands of extra-judicial executions, Mr Marcos stresses treatment for addicts. The police still shoot a lot of people, but the country no longer has a leader who says things like: “If it involves human rights, I don’t give a shit.” That probably makes investors less skittish about doing business there.

Mr Marcos has wooed foreign investment in improving broadband access, which is wildly uneven; congress is mulling a bill to spur more competition in this area. The roll-out of a national digital-identity system should make it easier for Filipinos to do business and get access to government services online. Since it began in 2020, roughly 70% of Filipinos have enrolled: impressive, though far behind the nearly 100% rate in India, a poorer country.

Like many of its neighbours, the Philippines worries about another Donald Trump presidency. His tariff hikes could hurt its exports of electronic goods. But it has handy sources of foreign currency that may be Trump-proof.

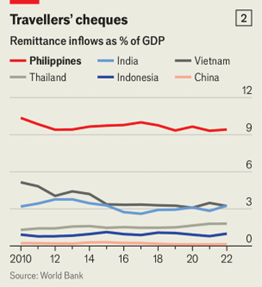

One is remittances from its 2m citizens working abroad, steering ships on the high seas or nursing patients in the Gulf (see chart 2). Though their numbers are equivalent to a mere 4% of the labour force in the Philippines, they send home the equivalent of 9% of GDP a year, a cash gusher that flowed steadily even during the pandemic. Remittances kick-start small businesses in every village. Norhaya Daud, a young mother in Cotabato, says she earned five times as much as a domestic worker in Qatar as she could have at home, and used the savings to buy land. Now she grows corn and coconuts, and runs a village shop.

Another Trump-proof source of dollars is tourism, which could boom when the airports improve. The Philippines has enormous untapped potential: warm weather, pristine beaches, coral reefs to snorkel over and a culture of hospitality. Yet it attracted only a fifth as many international tourists as Thailand in 2022, partly because it is so hard to get there. CLSA, a bank, predicts that annual tourist arrivals will soar from 5.5m in 2023 to 43m by 2030, and tourism revenues will grow from 9% of GDP to a hefty 22%.

The biggest threat to this cheerful scenario is geopolitics: the Philippines often clashes with China over its baseless claims to Philippine waters, and China’s government could warn Chinese tourists not to go there.

The third source of resilience is exports of services, which may be less affected by a future trade war than physical goods. With their fluent English and familiarity with baseball, Filipino call-centre workers are much in demand by American firms. The country’s business-process outsourcing firms employ more than 1.7m people. Jack Madrid, the head of IBPAP, the industry association, predicts revenue will grow by nearly 9% in 2024 to $40bn, as banks and health insurers move more back-office operations offshore.

Some expect artificial intelligence to destroy jobs in call centres, but Dominic Ligot, the head of research at IBPAP, doubts it. Today the industry’s growth is constrained by a lack of sufficiently skilled staff. ai could help make the less capable ones more productive, he predicts.

Obstacles remain. No farmer in the Philippines may own more than five hectares, so farms stay tiny and inefficient. Several laws discourage foreign investment: foreigners may not own stakes of more than 40% in a wide variety of industries, from public procurement to trading. Mr Marcos promises to ease rules on foreign ownership, but has met fierce resistance.

And the global environment is deeply unpredictable. When Mr Marcos visited the White House earlier this month for a summit with President Joe Biden and Japan’s prime minister, Kishida Fumio, he received a warm welcome. But Mr Biden may not be president next year, and Mr Trump could suddenly declare war on outsourcing. Relations with China, meanwhile, are dismal and could get worse. Nonetheless, “there’s a guarded optimism among businesspeople in the Philippines, despite everything that’s happening in the world,” says Mr De Larrazabal.

The articles may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third-party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for third-party material. Further, the information provided does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and so you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your personal objectives, financial situation and needs before acting on it.