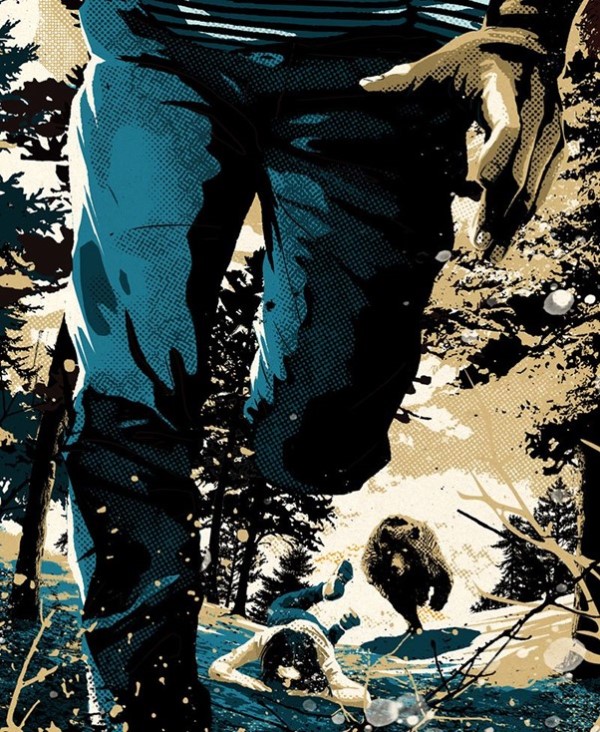

It began as a rewilding experiment. Now a bear is on trial for murder

This article was originally published on 26 April, 2024 in 1843 magazine.

Late in the afternoon of April 5th 2023, Andrea Papi decided to go for a run. The 26-year-old told his girlfriend that he would be home in time for a family dinner at 7pm. Then he set out through Caldes, a village of pale-pink houses dotted along winding mountain roads that lead down to a river.

Papi grew up in Caldes, which is in Trentino, an Alpine region in the far north of Italy on the border with Austria. He’d left to do a sports degree at the University of Ferrara and was now back home working odd jobs while he decided what to do with his life. He was tinkering with plans to open a gym in the village.

Running on the mountain trails around Caldes was one of Papi’s favourite things to do. It made him feel less stressed. That afternoon he crossed the river and turned up a boulder-strewn path leading into the pine forest that covered the slopes.

Dinner time came and went, with no sign of Papi. It wasn’t like him to be late, and at about 8pm his family decided to tell the mayor of Caldes, Antonio Maini, that he was missing. Papi’s parents, sister and girlfriend then gathered at the barracks of the local fire service, which co-ordinates mountain-rescue efforts.

A few hours went by. At midnight a more specialised search force of 100 people was assembled to start combing the mountains with dogs and drones. At 2.30am a rescuer found Papi’s water bottle on a path that school groups use on mountain hikes. A few minutes later the team came across his body. A broken and bloodied tree branch lay nearby.

Maini was called to the scene, and it was clear to him immediately how Papi had died. He felt he ought to go and inform the family of the death himself. When he broke the news, they barely reacted – it was as if they knew what to expect. They asked if it had been a bear attack, and it took all of the professionalism Maini could muster not to say yes. The cause of death couldn’t be officially determined until the autopsy.

When I asked Maini what the young man’s injuries had been, he declined to go into detail. Another local official was similarly reticent. He just said that bears attack people with the same force they use against other bears.

The mountains of Caldes are literally built from the bodies of ancient animals. The pinkish colour of its stone houses comes from the calcified remains of sea creatures – in prehistoric times, northern Italy was underwater.

The area is unusually rich in wildlife. It is dotted with lush vineyards, apple orchards and picture-perfect villages like Caldes. Eagles soar above the pine forests and Alpine chamois bound up sheer mountain faces to evade lynx and wolves.

The most revered creature in this panoply is the Eurasian brown bear, Ursus arctos arctos. Bears have lived here for as long as anyone can remember. They appear on restaurant signs and souvenir T-shirts. The people of Trentino are said to be bear-like, which in Italian lore means shy and taciturn. Legend has it that the local saint, Romedius, rode up a mountain on a bear and founded his sanctuary there.

Eurasian bears are only slightly smaller than American grizzlies. The smallest weigh around 140kg (around 300 pounds) and the largest over 450kg. They stand taller than most people. Their heads seem to span the entire four-foot breadth of their shoulders and they move with the powerful fluidity of athletes.

By the 1990s, the bears’ long history in Trentino seemed to be coming to an end. The population had dwindled to about four; no one was quite sure why. Bears, like people, move in and out of areas. Sometimes they start families, sometimes they don’t.

In 1993 the authorities running the largest conservation area in Trentino convened a meeting of international wildlife experts to discuss what could be done. One idea was to capture wild bears in Slovenia, where the population was flourishing, and resettle them in Trentino. Some experts wondered whether it would work, but everyone agreed time was of the essence, so the committee recommended the Slovenian strategy. Afterwards the regional government of Trentino adopted the policy, and received funding from the European Union (EU) to pursue it. In 1999 Trentino began releasing Slovenian bears into a stretch of forest not far from Caldes.

The term wasn’t widely used at the time, but one of the ideas informing the EU programme was what we now refer to as “rewilding”. Encompassing a range of practices from retiring your lawnmower to releasing pumas into a forest, rewilding rests on the premise that the more variety there is in a natural environment, the more resilient it will be. Human activities – building cities, razing forests, disgorging chemicals – have disrupted nature’s self-regulating systems. Rewilding promises to get them working again by giving the upper hand back to nature wherever possible.

One way this can be attempted is by bringing back the large carnivores that have been hunted to extinction in their original habitats. Their presence is thought to have a beneficial effect on the rest of the food chain (a concept known as the “trophic cascade”). In 1995 conservationists at America’s Yellowstone park tried out this idea by reintroducing wolves. The number of elk promptly went down, which meant there was more food for small mammals such as beavers, whose own population decline was reversed. Soon the park was being cited as an example of how to make biodiversity flourish (today scientists are questioning quite how much impact the wolves actually had).

Rewilding’s appeal cuts across the political and ideological spectrum. Some right-wingers love it for its implicit rejection of modernity; others revile it as yet another example of Brussels bureaucrats trampling over the concerns of ordinary people. There are rewilding advocates who see nature primarily through the lens of human needs. Others think it’s time humans learned they are just one species among many. For them the project is about more than trophic cascades: it is an act of penance and restitution.

At first the reintroduction of wild bears to Trentino didn’t seem as though it was going to be consequential. Few of them mated and the population stayed small. Then in the mid-2010s the numbers started to spike. The EU planners had estimated that the population would probably stabilise at about 50. By 2023 there were 100 adults and 20 cubs.

Bears are omnivorous, and forage and hunt mostly at night. They will eat berries, nuts, insects, fruit, fish, meat and nearly anything else they come across. Generally they try to avoid people, but this is not always easy. Trentino’s once-quiet mountains now teem with more than 30m tourists a year. Chance encounters between the two species have become more likely.

Male bears roam widely. Trentino’s have spread out across a vast territory that traverses the Austrian and German borders. After hibernating throughout the winter, they return to the females’ territory in the spring and summer to breed. The mothers raise their cubs alone. They defend them ferociously from male bears, who often kill the young of their rivals.

By 2010 Trentino’s bears were making regular forays into human territory, mostly in search of bins. The forestry department eventually sourced special, bear-proof bins – which the bears then worked out how to open.

One particularly large bear developed a habit of visiting homes. About 50 of them. Doors and windows were no obstacle. He just ripped them out, frames and all, with a casual flick of his long claws.

People began to worry, especially in the mountains, where memories of living alongside bears are closer to the surface than in a Brussels meeting room. To surprise a bear in a confined location, say by coming downstairs at night in response to the sound of a window being ripped out, means risking death.

The basic rules of such encounters are pretty simple. To resist a bear is as futile as squaring up to an avalanche. To run will only delay the inevitable. Bears sprint at 56km per hour (35mph) and won’t stop until the threat they perceive is quelled. Whatever illusions you cherish about how you might behave in this situation will be sorely tested. Tom Smith, a professor at Brigham Young University who studies bear-human interactions, cites one case in which a man surprised by a bear in the woods shoved his wife to the ground and ran away as fast as he could.

Campers and hunters in America are encouraged to carry canisters of bear spray, a form of pepper spray that is an effective repellent. But Italy classes this as a weapon, and doesn’t allow it to be sold to the general public. Instead the local government told people to lie down and put their hands over their neck if they encountered a bear (the logic, unstated in the official pamphlets, is this might help you survive a mauling with your head and vital organs intact).

The resurgent bear population didn’t threaten anyone at first. Then in 2014 Daniele Maturi, a cable-car operator, went out to forage for mushrooms near his home. Looking up, he realised that a bear and her two cubs were sleeping less than six metres (20ft) away from him. The bear’s name was Daniza, and she was one of the first Slovenian animals released into Trentino. Almost as soon as Maturi saw her she woke up, pushed him over with a paw and leapt on top of him. He survived only because she retreated. He still doesn’t know why.

In 2015 a trail runner out with his dog was surprised by a bear and had to be taken to hospital with serious injuries to his face, arms and chest.

Two years later, in July 2017, another man went out with his dog. He heard something behind him but as soon as he turned, the bear was on him. First it bit his leg, then it went for his throat. He managed to raise an arm to hold the animal off for a few moments. Then his dog barked, distracting the bear, and the man was able to get away.

Officials told reporters that they suspected it was the same bear in both instances – a 14-year-old female named KJ2. (The younger generation of Trentino’s bears are assigned identity codes based on the initials of their parents. Some end up being given names as well.)

The following month KJ2 seriously mauled an elderly man walking his dog. The Trentino government ordered her to be shot. LAV (the Italian abbreviation for the Anti-Vivisection League, an animal-rights NGO), called the bear’s killing “a shameful condemnation, a sentence without a trial, issued by a local authority that wants complete power of life or death”.

In 2018 the government of Trento, the largest province within the Trentino region, passed a law making it easier for foresters to kill bears that show signs of being dangerous. Animal-rights groups were furious, and escalated their complaints to the national government. They found an ally in the environment minister, Sergio Costa, a representative of the populist Five Star Movement. “You don’t shoot at wolves and bears,” Costa wrote on X (formerly known as Twitter). The Trento authorities were forced to back down.

In 2020 the forestry department captured M49, the bear who had been breaking into people’s houses. Because of the local government’s climb-down they could do nothing more than hold him at a secure veterinary facility. M49 proved a remarkable escapologist and twice overcame electric fences, among other security measures, to go on the run. Newspapers across Europe covered his antics and nicknamed the bear “Papillon” (after a famous prison-break film from 1973). Brigitte Bardot called for his freedom. Locals stayed out of the woods until he was recaptured.

Maurizio Fugatti, a member of Matteo Salvini’s right-wing Lega party, has consistently opposed the bear project in Trentino. In 2011 he attended a provocative banquet of bear meat, which the organisers said had been imported from Slovenia. Officials confiscated the cuts before any were consumed, but Fugatti said his attendance sent “a clear signal” of support to Italians denied access to their own slopes and forests because of the bear threat.

In 2018 Fugatti was elected president of Trento, but it was not until 2020 that his disapproval of the bear project started to be felt. That summer, a father and son were walking on Mount Peller when a female bear emerged, rose up on her hind legs and began clawing at the younger man. His father tried to help by jumping onto the bear. The animal, known as Gaia, broke the older man’s leg in three places before retreating.

Gaia was the fourth cub of two bears, Joze and Jurka, introduced into Trentino in the early 2000s. Her official name was JJ4. She was around 14 years old with three cubs of her own.

Fugatti ordered Gaia to be captured and killed. But he hadn’t reckoned on the power of social media, which helped transform her case into an international cause célèbre. Animal-rights groups appealed to the Trento Regional Administrative Court to stay the execution order. “We still don’t have enough elements to evaluate the bear’s behaviour,” the WWF told the New York Times. “Before we euthanise it, we have to better understand what happened.” In July 2020 the court sided with the activists. The campaigners released a statement expressing their joy that no one would be able to harm a hair on the bear’s head.

Giovanni Giovannini, the head of Trento’s forestry department, has been a ranger for more than 20 years. He has close-cropped greying hair, and gesticulates enthusiastically when talking about things like water conservation. He’d love his job to be focused on the science of woodland ecosystems. In reality, he spends a lot of his time responding to local concerns about bears.

By the spring of 2023 Giovannini had already written three reports to his superiors arguing that Gaia posed a threat to people, and should either be removed or killed. So when one of his employees told him a mauled body had been found near Caldes, where Gaia was known to live, her name flashed through his mind. Bear saliva had been found on Papi’s body, and when the authorities ran DNA tests on it, together with other genetic material they’d gathered, Giovannini’s suspicion was confirmed. Fugatti immediately reissued the order for Gaia’s capture and death.

Giovannini wasn’t sure which prospect he relished less: tracking down an intelligent bear and three cubs old enough to inflict fatal wounds, or the outrage from animal-lovers the hunt would inevitably provoke. His team knew roughly the extent of Gaia’s territory, and used cameras and other equipment to identify the best place to set up an ambush.

Their plan was to use a tube trap – a large metal cage, slightly taller than a person, with a bear-sized metal tube inside. The tube means that when the door slams shut, a bear has no corners on which to gain leverage to tear the cage apart or hurt itself.

Giovanni’s team decided to bait the trap with sweetcorn rather than a more alluring substance such as meat, because there was less chance of the scent attracting bears from other parts of the forest.

The rangers monitored the trap from home, via cameras and sensors, at all hours. If another animal knocked it over or moved it, they had to make the dangerous journey into bear territory to set it back in place. There were about 20 other bears in the area where Gaia lived. Every time a ranger turned his back on the dark forest to adjust the trap, he felt a tingling of primal fear.

On April 18th Gaia wandered into the cage. She was not enraged when the door slammed behind her, and didn’t put up a fight even when she was taken away and separated from her cubs.

Papi’s death sparked fury in the local area. Maini, the mayor of Caldes, started to receive hand-scrawled notes and Facebook messages, some of them threatening, demanding to know why he hadn’t protected his constituents. A pupil at his six-year-old daughter’s school told her that her father was a murderer.

People put up signs all over the village: “Justice and Dignity for Andrea”. Fugatti, the right-wing politician, turned up the heat, saying that Papi would still be alive if he had been allowed to kill Gaia in 2020.

Outside Trentino animal-rights activists were mobilising to prevent Gaia from being killed. They launched an appeal in Rome, and a court agreed that the bear’s death sentence should be commuted to confinement. Campaigners proposed she be relocated to a sanctuary in Romania. Legal wranglings over Gaia’s fate are still unfolding slowly between courts in Trento and Rome.

Throughout the process, animal-rights activists have been protesting outside Fugatti’s house (“Fugatti, we are all JJ4!” read one placard). Declaring themselves “anti-speciesism and anti-fascism”, Gaia’s supporters have also protested in Milan and Rome. They wrote to Maini too. (“You wanted the bears, now protect them.”)

“They all live on an ideal mountain,” Maini told me recently. “We have to live on a real one.” His village has been besieged by journalists from around the world, and the furore has caused him a great deal of stress. At one point his resting heart rate went up to around 200 beats per minute.

Papi is buried in the graveyard of a small church in Caldes. His grave is decorated with bright flowers, candles and a photograph of him on a mountain peak. Hanging on the front of a nearby house is one of the banners calling for justice.

At first Papi’s family stayed out of the maelstrom. Then, in July 2023, they issued a statement through their lawyer. It was brief but potent. The family expressed anger towards those focusing on Gaia’s welfare, and complained that local authorities still weren’t doing enough to keep people safe in the forest. Papi, the family said, was “a martyr to a political project that is now out of control”.

If you pick your way along a trail just outside the city of Trento, past the signs warning you to beware of wild boar carrying African Swine Flu, you’ll come to a large and extremely sturdy black gate in a fence topped with four strands of barbed wire. This is Casteller – an animal hospital and de facto prison. Gaia now lives here, along with Papillon, in limbo. Casteller has become a rallying point for protesters. They have even flown drones over the facility to report on the conditions in which bears are held. Gaia and Papillon have the run of 2,500 metre-squared pens, abundant food and excellent veterinary care, but the activists say this is a cruel substitute for the freedom of the forest.

One of the campaigners, LAV’s Massimo Vitturi, told me he had been allowed in to meet Gaia. It was an overwhelming experience for him. “To see the eyes with which she looked at me pierced my heart,” he said. “I felt the entire responsibility of the human species. I felt the need to apologise on behalf of all eight billion people.”

Those caught up in the struggle over Gaia’s fate have drawn surprisingly similar conclusions about the rewilding project. Vitturi is against it because he believes humans shouldn’t interfere in the lives of animals – the bears should never have been brought to Trentino from another country in the first place. Giovannini, the forester, agrees but for different reasons: it’s impossible to manage the bear population without culls, which are allowed to happen more freely in Slovenia. Maini, the mayor, takes issue with the very idea of “wildness” that campaigners revere. The forest itself is carefully managed, and no one objects to that. Why should the bear population be allowed to run amok?

I had spent a lot of time in Trento immersed in bears. I had read reports, heard wildly varying opinions, and listened to emotional accounts of encounters. I had seen bear videos and bear photographs, stuffed bears, plaster casts of bear footprints, and shiny plastic replicas of bear stools.

But I wanted to see a live Eurasian bear. To understand how it would be to turn a corner in the forest and run into one. So I visited the mountain sanctuary founded by Romedius, the saint who had ridden a bear. In his honour the sanctuary keeps a male bear named Bruno in a fenced-off section of the grounds.

At first, peering down from a raised terrace into a wooded enclosure ringed with stone walls. I could not see him. Then I realised he was almost directly below me, huddled next to the wall on a patch of muddy ground.

He was around 20 – past the middle point of a life lived at the whims of humans. First he was a circus bear, released from a tiny cage as a spectacle. Then he was rescued, and a decade ago he came to Trento, where he is evidently well cared for.

But he did not seem happy, to me at least. He was turning round and round on the spot, his great jaws slack and parted. Sometimes he rocked back and forth, palpably anxious.

His fur was a little damp, and I found myself searching for hope in that. I could not see how far his habitat extended. Maybe it sprawled. Maybe he could reach the mountain stream I had walked along to get to here. Maybe he got to feel wild and free as he hunted the dark trout, the length of my forearm, that I had seen cruising among the boulders in the glacial waters.

Then I realised the stream was too far away. There was a muddied water bath near his feet, no bigger than a child’s paddling pool. He had been attempting to wet his fur in it but had only partially succeeded.

The articles may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third-party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for third-party material. Further, the information provided does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and so you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your personal objectives, financial situation and needs before acting on it.